How Shadow Incentives Harm Real Security

Despite the millions upon millions of dollars thrown at penetration testing ever year, big data breaches are still as common as ever.

The security industry would not exist without bad actors.

Think about it for a moment. What is the point of a locked door if no one wants to steal? Any security team, product, or service exists only because there is someone out there looking to access systems that are not theirs.

Buying clothes, storing important documents, and conducting business with each other digitally are all lawful actions taken by regular people to fulfill some goal. Using the language of game theory, we can call this uninterrupted exchange of value cooperation.

Yet, we only have that word because of its opposite, defection. Without defection, there would be no cooperation. People would still do the sorts of things that we may consider cooperation, but there would be no need to call it anything other than simply living, working, trading, etc.

One cannot exist without the other. Cooperation cannot exist without defectors.

Security cannot exist without hackers.

So why do organizations so rarely invest in products and services like penetration tests in comparison to compliance initiatives?

And surely, if bad actors are the sole reason anyone spends money on security at all, those that understand how attackers work and what they do should have the most influence over improvement. And yet, penetration testing is at best, even now, an annual requirement by many compliance standards such as PCI DSS and ISO, and not even mentioned by some others.

The variable businesses are solving for is not improvement or resilience. It’s something bureaucratic and easy to digest, and it’s harming real security.

The World is a Business, Mr. Beale

“Why do businesses pay for SOC 2 reports?”

I froze for a few seconds, each of which felt like its own century. For my third day on the job at a company that, at the time, was primarily selling SOC 2 reports, this should have been a slam dunk answer for me. And I definitely thought it was.

“So they can stay compliant and prove they’re operating at a standardized security baseline.”

“Wrong”, said the founder who would eventually become my CEO.

Panic.

I had no idea, then. I had no clue why our customers bought our primary service which generated the majority of our revenue. Luckily, I was just incredibly naive, and was about to learn a valuable lesson that I would take with me forever.

“People buy SOC 2 reports so they can make more money,” he continued.

He then described what our compliance services were really about: a pipework of business-to-business relationships built on externally verifiable assurances and contingencies that, as far as I could tell, just kept any one organization’s skin from being the furthest into the game.

No, the goal was not to be more secure and improve over time. It was not to prevent breaches, it was not to better protect customer data, and it was not to mitigate business risk. Those were all afterthoughts.

The goal was to make more money.

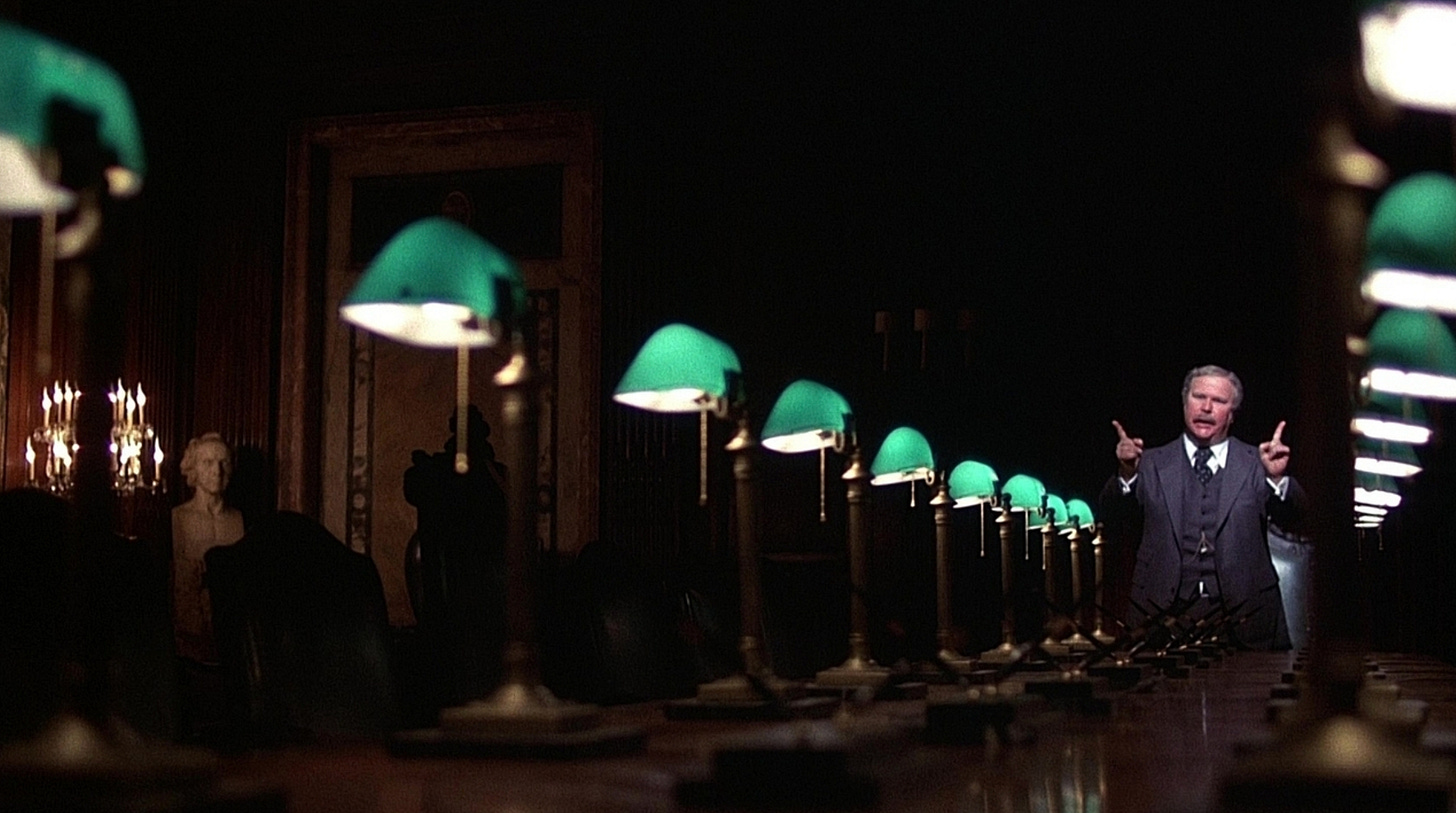

If you’ve seen Network (1976), this would have been when I saw the face of God if not for my near bulletproof idealism and naiveté, an inescapable brain cage native to my mid-20s.

Instead of in a shotgun blast revelation, ballistically delivered down the length of a solid wood conference table, the existence of shadow incentives in the security industry would slowly and painfully unravel itself across the landscape of my innocent mind over the next few years.

What I would eventually learn is that there is a race being run in security, but the finish line is not resilience or continuous improvement. It’s something contradictory, an antithetical box to be checked that is benefitting few and harming many.

Let’s take a step back and try to understand how, in security of all things, we’ve strayed so far from actually staying secure.

Where Do Penetration Tests Come From?

My fellow penetration testers and security researchers hate to think about what, to me, is a crucial part of the “buy security services” equation: most clients are only getting a penetration test or other vulnerability assessment of some nature because they have to.

When I ran the penetration testing practice at a previous employer, over 90% of our projects (and a similar percentage of our revenue) were what we called “compliance driven”, meaning that if we were performing a penetration test of an environment, it was because that environment was part of a compliance initiative scope.

If it involved a network, there was a good chance it was part of a PCI DSS card data segmentation effort. If it was purely external IPs and web applications, ISO 27001 was likely involved. The flow at my old company was simple:

A company wants to make money (e.g., via payment processing).

The company seeks out an external verifier (a PCI DSS auditor).

The auditor informs them that PCI DSS requirements mandate penetration testing of the scoped environment.

The company buys penetration testing services from the same firm as their audit services.

I get paid to attack a card data environment.

In this exchange, PCI DSS compliance via certification is the obvious answer to the dilemma of wanting to process card payments. For the purposes of my next point, it is one degree removed from the problem (a.k.a. “the solution”).

Penetration testing, being a requirement of PCI DSS, is two degrees removed from the problem. This second degree is emphasized by the fact that the skills required to audit a company for PCI DSS compliance and those required to perform penetration testing against a card data environment rarely overlap.

As with many things, the further a measure is from the problem it supports in solving, the more susceptible it is to “enshittification”, which is just a hot new phrase for a subset of the actions and consequences of a “race to the bottom”.

The Illusion of Quality-based Competition

Race to the bottom is a socio-economic concept describing a scenario in which individuals or companies compete in a manner that incrementally reduces the utility of a product or service in response to perverse incentives. This phenomenon is in contrast with traditional competition, which tends to improve goods and services.

Since penetration testing was (and still is, increasingly so) a rider requirement for many major compliance frameworks, I came to terms with certifications and attestations being a necessary part of the ecosystem, at least as it pertained to my revenue targets.

What I did not expect was how much we would need to compete with cost leaders, and how being a cost leader would invariably mean not being a leader of much else, namely work quality.

But to an auditor, a pentest report is a pentest report, and how much it cost the audited company is of no concern.

Outside of PCI DSS, organizations are often only required to provide evidence that a penetration test happened, either in the form of a heavily redacted/abbreviated report or a simple letter of attestation from the firm that did it.

When compliance depends on admittance, and admittance only depends on occurrence, and occurrence doesn’t depend on cost, the race to the bottom begins.

The areas over which many pentesting teams compete are no longer the coherence and robustness of the deliverable, the rigor and depth of the methodology, nor the relevance of the findings. Instead, they compete over cost and delivery time.

And when lower costs and faster delivery are the winning traits, everything else naturally suffers.

What To Look for (if You Care)

Everyone has to make a choice when paying for security work: quick and cheap, cheap and good, or good and quick.

At this point, it should be obvious that cheapness is a reliable indicator of lowered quality, though the inverse is not as reliable. An expensive service is not reliably a good service.

Cost is a metric on which different providers can easily compete, but why lower your prices until you’re forced to, either to match a competitor’s pitch to a prospect or to simply pull in more leads from the start?

Even more dastardly is the inflationary cost competition strategy by which a provider constantly markets themselves as “bleeding edge” or “constantly innovating” in order to make their pentesting methods to be the most relevant, while not adding anything of real substance at all.

The best example of this is when, before LLMs were as impressive as they are now (a meager five-ish years ago), and the marketing term was “machine learning”, vendor after vendor was shoving “AI” into their firewalls, IDS, and EDR, just hoping you wouldn’t ask them what that actually meant.

An expensive service doesn’t guarantee a high quality product, but very rarely is a high quality service not expensive.

Apart from playing the cost guessing game, to know you’re looking at a higher quote with guarantees behind it, check for any of the following:

Expertise on Display

Blog posts are ubiquitous. Quality writing is not.

Look for where your prospective vendor actually talks about what they do and why. Do they discuss their methodologies and why they do things? More interestingly, are there things they’ve opted not to do?Sample Deliverables

Get an example report. If a vendor can’t give you one of these, they’re either not proud of their results or are not committed to standing out.Good reports aren’t some kind of proprietary knowledge or insider information. Competitive advantages though they may be, they’re also the the table stakes and shouldn’t be some secret they keep close to the chest.

Recognizable Customer Testimonials

It has never been easier to generate fake testimonials. LLMs are very good at this, so verify the people and their respective companies are real.

Customers actually willing to vouch for a vendor is a strong indication that the service is good.

The bottom line is that, if you’re looking for a pentest report that is going to fulfill a compliance requirement without any scrutiny, just about anyone will do.

If you’re looking for security professionals that can make positive change and help improvements stick, you might need to look toward the top of the barrel.